<< Back to EBOW overview for all institutions

We took a deep dive into libraries for three years, with the support of IMLS and as part of our Engaging Beyond Our Walls project. Below is some of our justification for that effort and framing of the project.

Jump ahead to:

- Overview

- The need for libraries to go beyond their walls

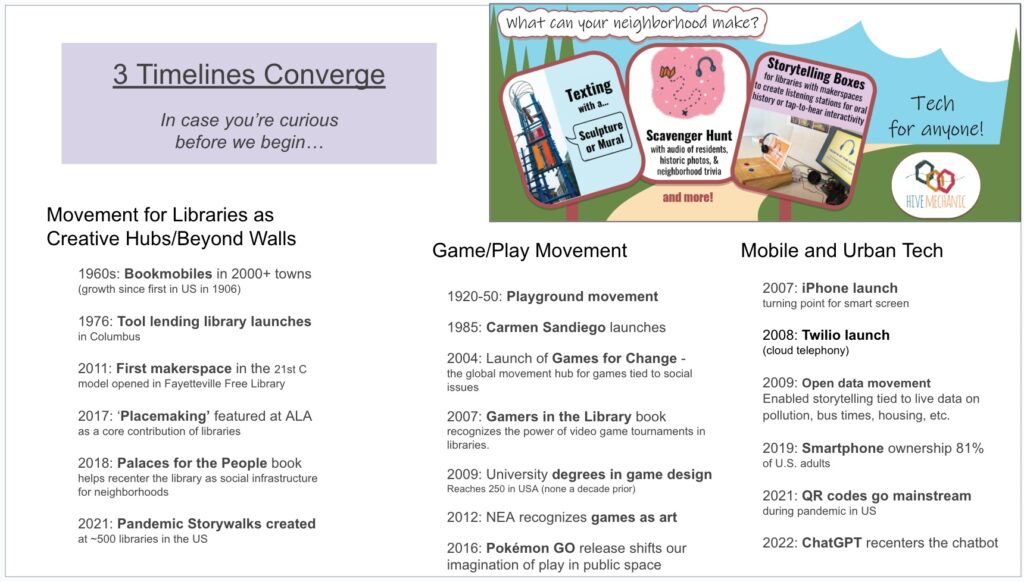

- Timelines converge: libraries as creative hubs, game/play movement, mobile+urban tech

Overview

Beginning in 2021 (see our initial announcement), this three-year project has trained libraries in 60+ cities and towns to make neighborhood games and branching stories for community engagement. The experiences were proudly low-tech, including: mural hunts, audio tours with local voices, puzzles with local history, texting-with-a-sculpture, book walks, and architecture scavenger hunts using camera phones.

These are games and activities that can be played with ordinary cell phones, and typically without a fancy smartphone. Our dream is to diversify participation in local storytelling by supporting rural and small libraries, and by centering local voices in all game and story content. We use text and multimedia messaging, which do not require data plans or wifi. (Text and multimedia messaging are increasingly unlimited for most phones, and are separate from data plans to access the internet.) Low-tech is an unusual approach for game design, but one that is essential for increasing access and meeting the equity goals of public libraries. With this project, libraries have leveraged their core strengths in media literacy and their roles as local information brokers, increased access to game design, and helped to bridge the gap between local history in local archives and interactive media.

Previously, the model was piloted in installations with the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, the DC Office of Planning, and community arts spaces like Tephra in Reston, Virginia. The core library partner has always been the DC Public Library, from early pilot projects to co-designing the curricula and disseminating the project publicly.

IMLS funding for the project has supported training for the past three years, along with the free and open-source tool to create these experiences, the curriculum, and the text messaging fees. Our open-source authoring tool is called Hive Mechanic, and was developed for cities by the Playful City Lab at American University.

I. NATIONAL NEED TO GO “BEYOND OUR WALLS”

The need to meet the public beyond library walls is growing rapidly. Gentrification and neighborhood change redoubles the need to know our local history – and hear local voices. The demand to give voice to community history and local culture has never been higher – including in public space.

Local play offers a distinct pathway to civic engagement: research shows how local play can connect us more deeply to our physical streets and local history, and can provide an excuse to talk to neighbors we don’t yet know.[1] When American University hosted “Libraries, Games, and Play,” an IMLS-supported conference in 2019,[2] we identified a striking finding that most libraries lack the capacity to engage with game design, especially for local community use. This project helps pave a new path for public libraries to be hubs for civic play, inspired by the long tradition of bookmobiles, the intergenerational play of Pokémon GO, and innovators like the Free Library of Philadelphia branches that remixed play to engage the public with local art.[3]

This project addresses three immediate needs currently lacking in public libraries: (1) basic training and curricula in game design for communities; (2) access to templates of successful community games to simplify design, and greatly reduce barriers to scale; and (3) free authoring tools like Hive Mechanic that are easy enough for non-technical users to create games. Budgets today are tighter than ever, and digital divides are growing. Wifi is not available in public space, but games with Hive Mechanic work for text and multimedia messaging on basic phones. Just as importantly, the games in this project can be created and played for free, without any programming skills – and still provide an optional starting point for those seeking a STE(A)M trajectory.

Traditionally, game making in libraries has emphasized indoor and desktop media, from Minecraft to Scratch, often focused on youth in STE(A)M initiatives[4]. By contrast, we insist on play and engagement that is primarily outdoors and features community assets and voices in public space. During the pandemic, for example, outdoor “story walks” have surged in popularity at libraries[5], yet they are almost exclusively analog — and not interactive. Compared to museums, libraries lack basic resources for interactivity in their public programming, especially outdoors in community spaces. Libraries are often the only civic institution at the neighborhood level with civic and community content — especially across digital divides.

COVID-19 only confirmed the importance of libraries meeting the public beyond their walls. Subsequent protests around systemic racism and reform were also often focused on public space and local control over public streets. Libraries are facing a high-priority gap in technology to engage the public beyond their walls, including to bring digital archives to wider audiences and to cross digital divides. As restrictions on social distancing ease, libraries are rethinking their outdoor programming — and connecting the old and new. Murals and public art, for example, already reach different and wider audiences than many library events, and are visible at all hours of the day. It is time to empower our communities to tell interactive stories with our digital archives and resources that cross digital divides.

For libraries of the future, an “indoor only” strategy for engagement will be incomplete. So many stories of our communities, including racial justice and gentrification, demand to be told in the same public spaces they critique and address. How we empower our communities to tell these stories matters, and will affect local resilience, community decision-making and investment for years to come.

2. Conceptual timelines converge

[1] See our 2020 book from MIT Press: “Locally Played: Real-World Games for Stronger Places and Communities”

[2] A total of seventy-five participants attended. The conference also included a showcase of exemplary library game projects, and keynotes from leading librarians and game designers.

[3] See our 2018 report on the Philadelphia model: https://playfulcity.net/go/pokemon-report/cities/philadelphia-libraries/

[4] For example, see the IMLS support in 2013 to recruit libraries and youth for the National STEM Videogame Challenge.

[5] Libraries in 50 states have done a StoryWalk, according to the “Let’s Move in Libraries” project of UNC Greensboro, including more than 300 libraries since 2017; the model was created by Anne Ferguson in 2007. https://letsmovelibraries.org/storywalk/