[Updated April 11, 2022 with new images]

Communities with purely analog wayfinding may increasingly lag, as mobile media begins to dominate real-time wayfinding and drive the storytelling of place. Already, we know that wayfinding can be a way to create a strong sense of place, including spark business investment and cultural cohesion. In hybrid wayfinding, the process of selecting content to represent the neighborhood can have real benefits too, as stakeholders come together to review priorities and articulate cultural assets — ideally in their own voices.

In 2021, we installed five signs along the Pennsylvania Avenue East corridor — a neighborhood that is about to receive new investment, thanks to a new small-area plan and a newly-launched “Main Streets” program. Each sign comes with a QR code “for more” resources tied to that place and a related editorial theme.

This diagram shows our model:

The system works as follows: a local resident walking along Penn Ave SE might notice a physical sign about “Black Owned” businesses (a point of pride for the largely Black neighborhood). She is curious to learn more and scans the QR code, which opens our Penn Ave SE website on her phone.

Once on the site, a visitor would then discover a map of the neighborhood, surprising her with a location she didn’t know about — and now intends to visit. She leaves feedback on one page with a business she feels was overlooked, and mentions the site on social media to her friends and neighbors.

Social media can amplify the digital side of the wayfinding system (unlike purely analog signs). Here is one unsolicited example from the local Main Street group:

Wayfinding systems have both informational and storytelling functions. When local organizations like Main Street start using the system to tell the neighborhood story, we consider the system at least a partial success.

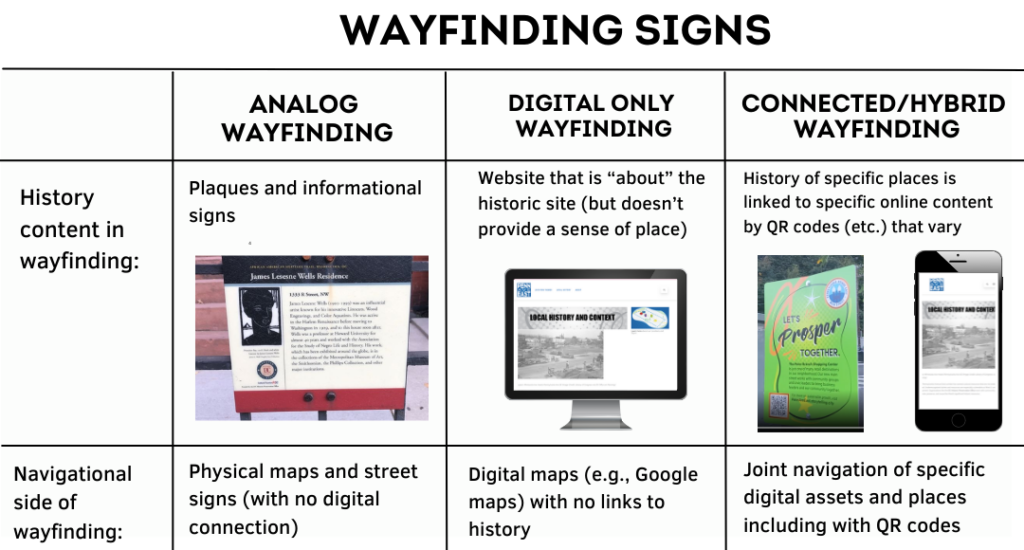

Hybrid is different than pure analog AND different than pure digital. One way to see the contrast is in this table:

We grounded our approach in research on “strong neighborhoods” that can tell their own stories, especially when residents are connected to local news and civic organizations (see: Communication Infrastructure Theory (CIT), which originated in the 2000s in Los Angeles). CIT provides a model for strengthening local communities at the level of social infrastructure and information flows — which can be far cheaper than physical infrastructure, and at times more empowering. The ability to identify local assets, both economic and cultural, is at the heart of community-based empowerment and cohesion.

Can we take this idea further? A few provocations:

- Should the process of selecting the neighborhood brand and story be jointly a function of city planning and community organizing?

- How can planning departments help to ensure the neighborhood is not left behind in a digital age (while also ensuring that access includes residents without internet)?

- As the role of libraries shifts at the neighborhood level, are they the best convening locations to periodically update the content of wayfinding systems?

- How is the balance between utilitarian navigation and cultural history/placekeeping best negotiated by stakeholders?

- Finally, innovations in wayfinding can come from anywhere — but should they perhaps be piloted in historically overlooked neighborhoods, rather than the usual tendency to let them emerge in wealthier neighborhoods?

Additional Readings and References:

- The Society for Experiential Graphic Design describes “Wayfinding” as information systems that guide people through a physical environment and enhance their understanding and experience of the space.

- A Brief History of Wayfinding

This post was jointly contributed by Benjamin Stokes, who directs The Playful City Lab at American University, and Tambra Raye Stevenson, MPH, a Ph.D. student and research assistant at the American University School of Communication in Washington, DC.